History

Middle Ages

Monastery of Sant’Angelo

A new thriving organization arises based on the Benedictine Rule.

8th Century

The organization of the Terra Sancti Benedicti

Between 796 and 817, the abbot Gisulfo, like his predecessors, dealt with the reconstruction of the Abbey of Montecassino, destroyed for the first time in 577 by the Lombards of Zetone. He established the new borders of the Terra Sancti Benedicti1, which had reached a considerable extension thanks to Duke Gisulf II of Benevento, who in 744 donated to the abbot Petronace a vast territorial portion around the abbey1-2. Gisulfo also took care of the land reorganization of the monastery’s estates and took on the urgent spiritual assistance of the surrounding populations1-2. For this reason, he reclaimed a marshy area near the Rapido, enlarged the monastery of the Saviour at the foot of Montecassino and established the manorial organization in the Land of Saint Benedict with the construction of the cellæ2.

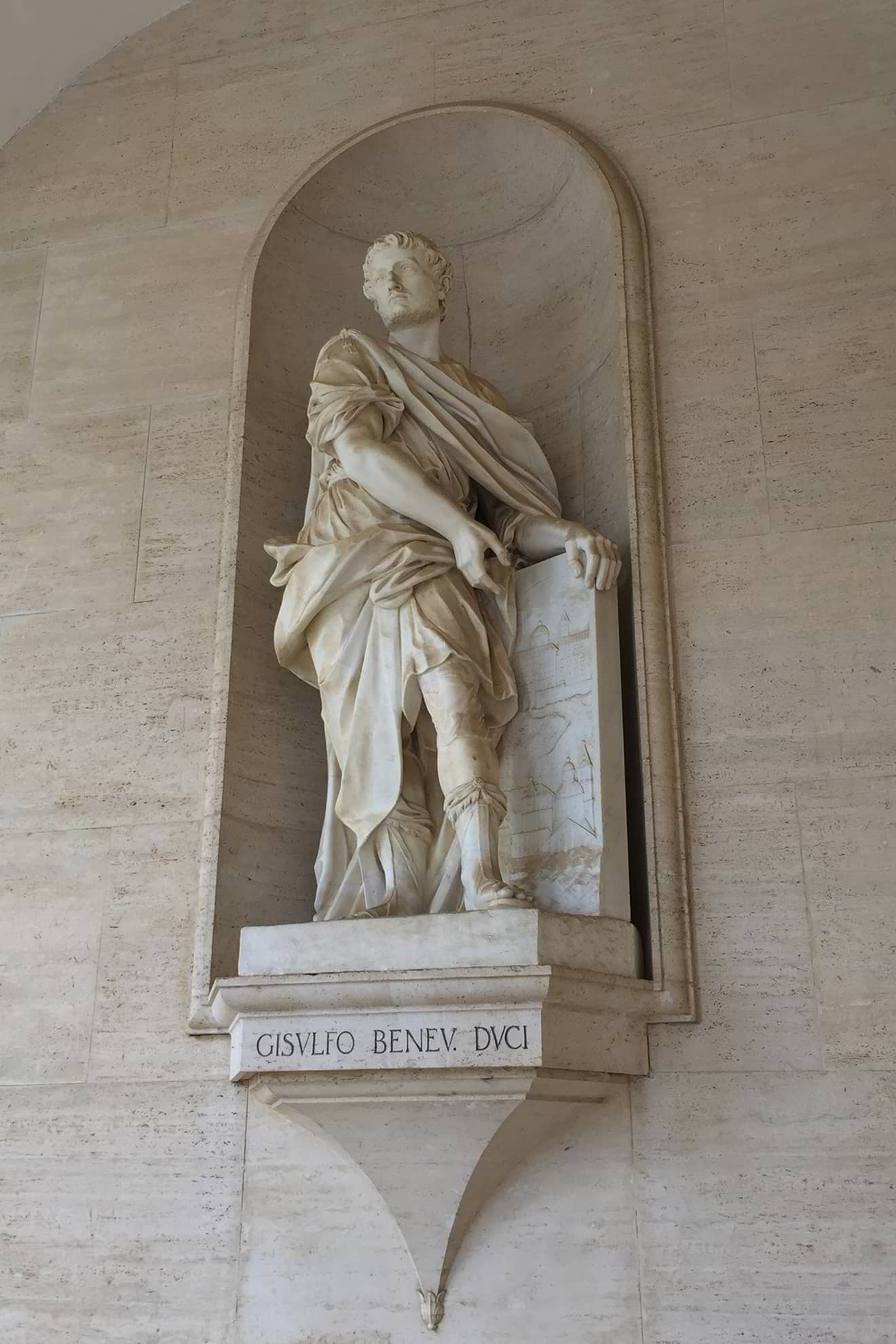

Photo: Duke Gisulf II of Benevento, 1666, marble, Cassino (FR), Abbey of Montecassino, Cloister of the Benefactors.

8th-9th Century

The Cellæ

The cellæ, also defined as “minor churches” or “small monasteries”, were Benedictine organizations based on the manorial system where peasants could work and take part of the harvest1. The first cellæ that arose in the Land of Saint Benedict were the cella of Sant’Angelo in Valleluce and the cella of Sant’Apollinare in the “Albiano” locality. Each one of them constituted a curtis and the monastery of the Saviour served as a curtis maior, on which they depended3. For their foundation, the most fertile or most populated areas were chosen, in order to assist as many inhabitants as possible. Among these there was also a skilled workforce, capable of carrying out the work that the artistic enterprise required1-2. Valleluce, however, was certainly chosen because it was hidden by the hills, which made it safer from possible incursions3.

Map: Emilio PISTILLI, From the Land of S. Benedict to the Diocese of Sora, in “Studi Cassinati”, 2016.

8th-9th Century

Structure of the Cellæ

To each cella there were land annexes divided into different types. The first land was the pars dominica, worked directly by the Benedictines of the local coenobium or by employees called “angarari”, who were obliged to lend a certain number of working days during the year called “angariæ”. The second was the pars massaricia, intended for the colonists and the free peasants who gave part of their harvest to the monastery. Finally, there were the partis pertinentiæ, consisting of woods, meadows and pastures that satisfied the primary needs of the inhabitants2-4. This economic organization, somehow, was the continuation of the agrarian system of the ancient pagus3. In this way, each cella guaranteed itself a self-sufficient economy which, not surprisingly, corresponded with the spirit of the Benedictine Rule itself2.

10th Century

Encastellation Era

Less than a century later, the manorial system was suddenly interrupted after another ferocious invasion; this time by the Saracens who, in 883, sacked the cellæ and destroyed the Abbey of Montecassino for the second time. The forty years that followed these events were marked by a great insecurity, a social crisis and the retreat of cultivated areas. After the victory in the Battle of Garigliano in 915, there was a resumption of control over the territory. In 967 Prince Pandolfo I granted the new abbot Aligerno the Ius Munitionis, which was the right to freely fortify the inhabitants of the Terra Sancti Benedicti. The cellæ became the main fulcrums of the repopulation and the base of the castrum2.